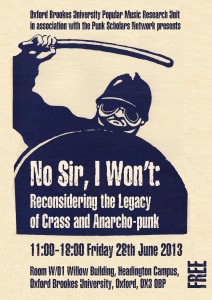

Here is the poster for a forthcoming symposium reconsidering the legacy of Crass and Anarcho-punk.

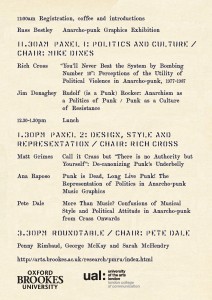

I will be delivering a presentation on the Alexander Oey documentary ‘about Crass called ‘There is No Authority but Yourself’. There will also be a round table discussion at the end of the symposium with Penny Rimbaud one of the founder members of Crass. Interestingly enough at a recent talk he gave at a film festival in Southend -On-Sea he said that he wasn’t too enamored by being asked to attend academic conferences- see his comments amongst other interesting insights here http://thehippiesnowwearblack.wordpress.com/category/penny-rimbaud/ on Richard Cross’s fantastic blog. All the same Penny apparently is still coming which is great news.

Here is the abstract outlining what I will be discussing

Call it Crass but ‘There Is No Authority But Yourself’: De-canonizing Punk’s Underbelly.

Matt Grimes

“But if punk stops in 1979, then it can be argued that that there is a great deal of the story left out. This includes punk offshoots such as…. the anarcho-punk movement, with bands such as Crass who took the anarchist message seriously…”[1]

Roger Sabin’s analysis of the histories of punk is very telling. It is in this context, of how histories of popular music are constructed, documented and presented, that this paper examines the documentary There Is No Authority But Yourself (2006) directed by Dutch director Alexander Oey concerning the anarcho-punk band Crass[2]. This documentary is important in providing an analysis of a band which has been mostly excluded from a standard story of popular music, and even from more focused examination of punk as a broader musical genre. Discussing the documentary, therefore, allows us to engage with a neglected part of music history.

In this essay I link the issue of documentary style to questions about documentary as historiography. By this I mean how documentaries are used as a way of presenting and documenting history– specifically how we find out about and present the history of popular music, with a focus on punk rock, for the screen. I intend to use Oey’s film to go beyond the classification of televisual representations of popular music as “rockumentaries”[3]. To do this I distinguish between what I am describing here as ‘standard music histories’ exemplified by the BBC’s Britannia[4] series, the avant-garde approaches taken by Don Letts and Julien Temple, and the approach typified by Oey. Generally, I want to suggest that the first two approaches, for all their differences tend to represent popular music histories, through the utilisation of what can be seen as the canonical processes that contribute to the formation of a ‘punk’ canon. In doing so I suggest we need to reconsider the role of canons in the construction of popular music histories.

[1] Roger Sabin, ed., Punk Rock: So What? (London: Routledge, 1999), 4.

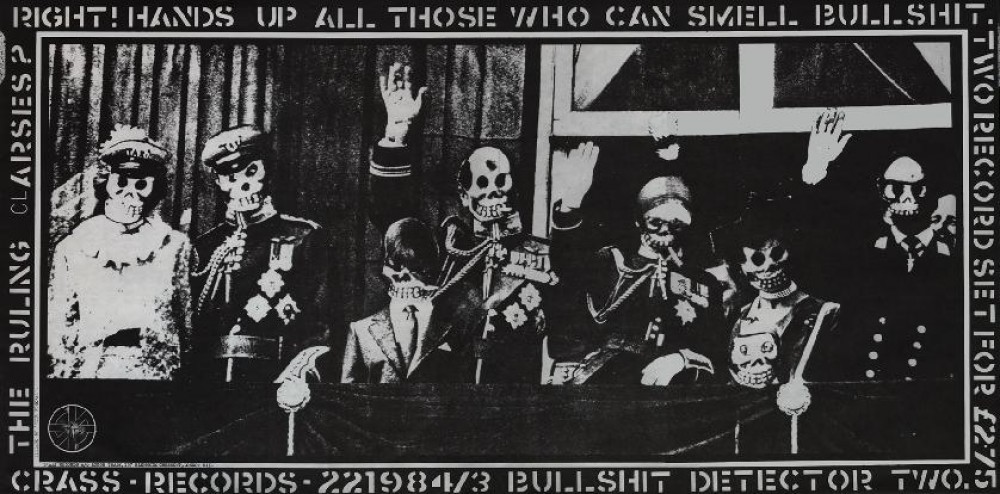

[2] Crass were an avant-garde English punk rock band formed in 1977 around a collective of musicians based around Dial House, an open house community in Essex. The band was formed as a direct response to what they saw as the failings of the then popular punk movement to live up to the DIY (do it yourself) and anarchist ethos often espoused by artists such as The Sex Pistols, The Clash et al. Crass were seminal in the development of anarcho-punk, a specific subcultural strand of punk rock that promoted anarchism and pacifism as a political ideology and a way of living. Members of the band continue to perform under various collaborations and individual performances.

[3] a term first used by Bill Drake and Gene Chenault producers of the 1969 93 KHJ Los Angeles syndicated radio documentary The History of Rock & Roll

[4] The Britannia label consists of a series of documentaries and one-off programmes produced by the British Broadcasting Corporation about the history of popular music and their related cultural activities in the UK