I recently attended the second Punk Scholars Network (PSN) event hosted by Dr Matt Worley and the School of Humanities at Reading University. The PSN, of which I am a member, has been in existence for approximately 8 months and is a collection of academics, and some non-academics, that have an interest in researching and investigating punk and its many musical, cultural, social and political facets across many disciplines of study and research. This event was titled Punk In Other Places: Transmission and Transmutation and entailed a collection of presentations considering punk, its global ‘reach’ and localities.

The first presentation was from Hilary Pilkington (University of Manchester) who discussed an ethnographic study of a punk scene in a post-industrial post USSR town (of which the name eludes me) in Russia’s arctic hinterland. Described by the local punks as a ‘rotting city’ Hilary’s study followed a group of local punks and examined in what ways the group defined themselves as ‘punk’ and how that particular subcultural group negotiated their place within the city and alongside other subcultural groups. The particular town was in both industrial and social decline and many young people would leave and move to larger metropolis, whereas some, including this particular group of punks, decided for one reason or another to stay. One of the interesting things to come out of the study was how the many subcultural groups in the town would share places, spaces and resources within the city to maintain their scene. Despite the groups were fundamentally different in their music and style they appreciated that due to a lack of investment and resources they were having to renegotiate their subcultural boundaries in order for each of those scenes to survive.

The second presentation was from Jim Donaghey, a PhD candidate from Loughborough University who is researching his PhD around notions of anarchism within punk scenes in UK, Poland and Indonesia. In this particular presentation he discussed some of his findings from a recent visit to Indonesia where he was conducting an ethnographic study of Indonesian street punx (sic). His study highlighted how 2 particular groups of street punks expressed their punk aesthetic, anarchistic beliefs and politics in a country with a regime that was both extremely politically and religiously (Islam) repressive. Marginalisation, discrimination and physical intimidation were regular themes that came out in his work, but despite this there is a sense of positivity and deep comradeship within the punk scenes he is investigating. Those scenes are deeply immersed and entrenched in the DIY principles of punk as access to media and resources to support them are barely available and would also bring them to the attention of the authorities that regularly clamped down on any youth cultures that fell outside of the ‘norm’ in both the eyes of the authorities and the local religious leaders. You may have read last year in the Guardian newspaper about groups of street punx in Indonesia being rounded up by the religious authorities and sent off to ‘ youth boot camps’ where they were ‘de-punked’ (heads shaved, piercings removed etc.) and ‘re-programmed’ (religiously and socially) before being returned to society as a ‘normal model citizen’. Quite repressive and disturbing.

Following on from Jim was a presentation by Melanie Schroeter of Reading University who discussed the issue of racist and xenophobic lyrics in German punk song lyrics of the nineties. Applying discourse analysis to the lyrics she highlighted the relationship between German punks and the asylum debate following on from the fall of the Berlin Wall and series of racially motivated attacks on hostels housing immigrants.

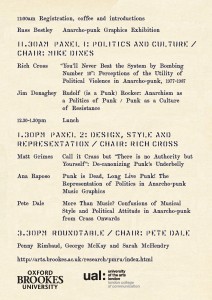

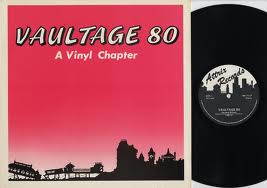

After an agreeable lunch Russell Bestley, from the London College of Communication, gave a fascinating presentation on the visual imagery of punk (predominantly record sleeves) and its relationship to regional locations. Decentralizing London as the home of punk he demonstrated how punk bands from regions around the UK would use local landmarks, such as street signs and known buildings, as backdrops for the covers of the records released by those bands to firmly locate them in their region. He argued that this was partly done to show that London didn’t ‘own’ punk and that punk and its scenes were existing and flourishing in other parts of the country, despite media rhetoric about it being a London phenomenon. It was great seeing some of the old record sleeves including the Vaultage series from Attrix Records, that had all the Brighton/Sussex punk bands showcased- I was part of the punk scene that developed around The Vaults ‘venue’ which was a crypt below an old church in the centre of town

Following on from Russ was an interesting talk From Pete Dale who started his discussion around Scottish post-punk by delivering a searing critique of Simon Reynolds and his work on post punk and how Reynolds attempt to locate his work in academic theory and theoretical grounding failed-I can’t quite remember the full content of what Pete said but I remember it being controversial and received some nods from the audience. Note to self: remember to take a digital audio recorder to future events.

Last up was Paul Harvey who discussed his journey from playing with Penetration (a great Scottish punk band who I was/is still a fan of) to academia. His story was one of reticent acceptance into the academy but came about from his excellent PhD that linked Stuckist art to punk through questioning the whole concept of authenticity,what makes punk ‘punk’ and punks relationship to Dadaism and the Situationist movement. I thought his deconstruction of notions of authenticity in punk through the questioning of memory and what he referred to as ‘fabricated cliches’ was insightful.

All in all a great afternoon where I met some really interesting scholars and am really looking forward to the next one.